Less Involution, More Innovation: Why China Is Tackling Nèi Juǎn?

This article is composed of paragraphs from Zhejiang Publicity, People's Daily, Study Times, and Capital News.

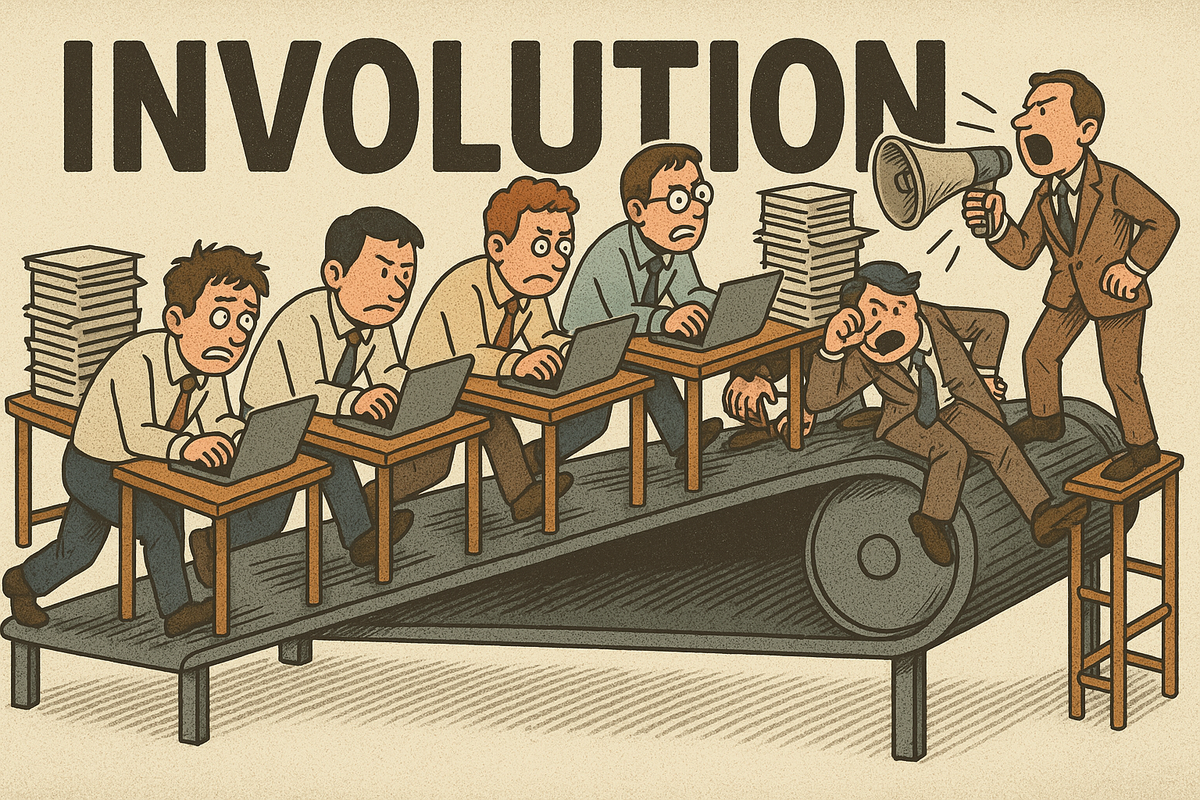

In the 1960s, anthropologist Clifford Geertz coined the term “involution” to describe a pattern of agricultural development on Indonesia’s Java Island, where labor input kept increasing but productivity did not. Although few people acknowledge the origin of the concept of involution, the word has gone viral in China’s social media and society for years. Actually, in China, the public hype for using the word “involution” (“内卷” Nèi Juǎn) initially started from the education sector.

Historically, Chinese society has always placed a high value on education. Ancient poems described scholars studying under dim oil lamps at midnight, and the story of “Mencius’s mother moving three times” (“孟母三迁”, Mèng Mǔ Sān Qiān) is widely known. According to records over two thousand years old, Mencius’s mother relocated their home from beside a cemetery and then a slaughterhouse—both unsuitable environments—to a place near a school, hoping to give her son a better upbringing. It is believed that these moves significantly contributed to Mencius’s later success as a great thinker.